The Hail Mary in Our Final Season

In the last season of my father’s life, I made a quiet decision to throw one final pass. Here's what happened...

The Unexpected

My father passed away on Father’s Day, three years ago.

I was set to leave for Venice the next day.

As the time got closer to my leaving, Dad kept calling, anxious, asking me when I’d be back.

Each time, I assured him that while I was in Italy, I’d call him multiple times a day.

The day before he passed, sensing his anxiety, I phoned in to reassure him, “Hi Pop, How ya doin’ out there? Listen, don’t worry, I’ll bring you with me in the boats. I’ll call you via FaceTime from a gondola,” I said smiling.

Normally, that kind of play would disarm him, and we’d have a good laugh.

But this time, he maintained his concern.

I knew ‘cause I saw his furrowed brow on the screen.

Plus he didn’t say much.

You think he knew?

I’d been care-giving Dad for years, and the idea of a week off with cappuccinos, art, and “tutto bene” sounded like heaven.

Heading back on the train, watching the New York landscape whizz by out the window, I find myself thinking of him.

The Gladiator Years

I remember the times when I’d visit him at his elder care facility.

I won’t sugar coat it; that place was depressing as hell.

The people there looked like variations of petrified wood.

Seriously.

Their robotic movements both connected and disconnected.

Pasty food, often drooling from their mouths, made it look like the zombie apocalypse was about to kick off.

One time, when I was sitting in the dinning hall, I was introduced to a woman at Dad’s table 6 times in one dinner.

Every 5 minutes, she’d turn to me saying, “Who are you dear?”

Everyone treated it like it was quite normal, and kept on eating.

I got used to it, but let’s just say, thank goodness I have grounding in reality.

Anyhow, during that time, I was heading upstate twice a week to see him, bringing snacks, the papers, and some love.

A Thing of Beauty

The day I’m remembering, we were sitting there shootin’ the breeze.

Dad liked to talk about sports, anything Italian, the family, days gone by, and local politics.

He was telling me about a conversation he’d had with my brother, Carl, about a football game and something about a ‘Hail Mary Pass.’

“What the heck is a ‘Hail Mary Pass?’” I asked.

Dad loved to explain details in sports.

“It’s called the Roger Staubach ‘Hail Mary Pass,’” he said, carefully annunciating ‘Staubach.’

“It comes from a game when Staubach threw a winning touchdown to Drew Pearson in the last seconds of the 1975 Division Playoffs between the Dallas Cowboys vs the Minnesota Vikings.”

"The Cowboys were down, when Staubach threw a long pass to Pearson. Astonishingly, Pearson caught it, as he was colliding with another player, and fell into the end zone for a 14-10 victory. Staubach, in his post-game comments said, “He threw the ball as a prayer.” After the game, when the news people asked him, Staubach said, "I just closed my eyes and said, a 'Hail Mary.’

From then on,” Dad said, “The term ‘Hail Mary Pass’ was on the map, as a description for a last-effort pass in a football game.”

As Dad was explaining, I picked up an old beige album of photos that was resting on a chair. Seeing me grab it, he said, “Aunt Pat dropped that off the other day. There’s some old photos of mine in it. Take a look.”

Opening it, I began thumbing through the sticky pages. Inside, I found old photos I’d never seen before, of dad, his siblings, and his parents, when they were young.

Every few minutes, as we talked, I’d hold up an image, asking him, “Who’s this? Where was this?”

Dad would turn from what he was doing at his desk and look.

Then he’d say, “Oh that’s our dog Brownie, or that’s Nonnie and Pop at a New Year’s Eve costume party. Nonnie went as the Statue of Liberty, or that’s me and uncle Bobby, what fun we had that day, or that’s your great aunt Mary, you remember great aunt Mary, right?”

Holding up a photo of a big group of people at a long table full of food, I asked, “Where was this?”

“That’s at Grandma’s house. Well, your great grandma, Pop Pop’s mom’s house 338 Roosevelt Ave, in Jersey City. We went there every Sunday. Pop Pop went to see his mother every week. The food at those dinners was endless. So many courses of incredible Italian food came out of that kitchen. The antipasto, the main course. God, the food never stopped. Aunt Tessie would be in the kitchen with Grandma the whole day, just cooking.”

“Sounds so fun. Did all of Pop Pop’s siblings come too?” I asked.

“Oh sure,” he replied. “Nobody missed those Sunday dinners.”

Holding up a perfectly square photo, I asked, “And this one?”

Dad squinted, leaning in, and said, “That’s Pop, with his best friend Dr Semisa, at our home on Palmer Ave.”

We sat in silence for a moment then Dad said, “My whole childhood, I never went to a doctor. Semisa always came to our home, if we were sick...”

“What?! You never went to a doctor’s office as a kid?! Really? Wow. I didn’t know that,” I said.

Dad nodded at the fact of it, as he said, “That was Pop and Semisa’s deal. Pop did all Semisa’s family’s legal work, and Semisa took care of Pop’s family’s medical.”

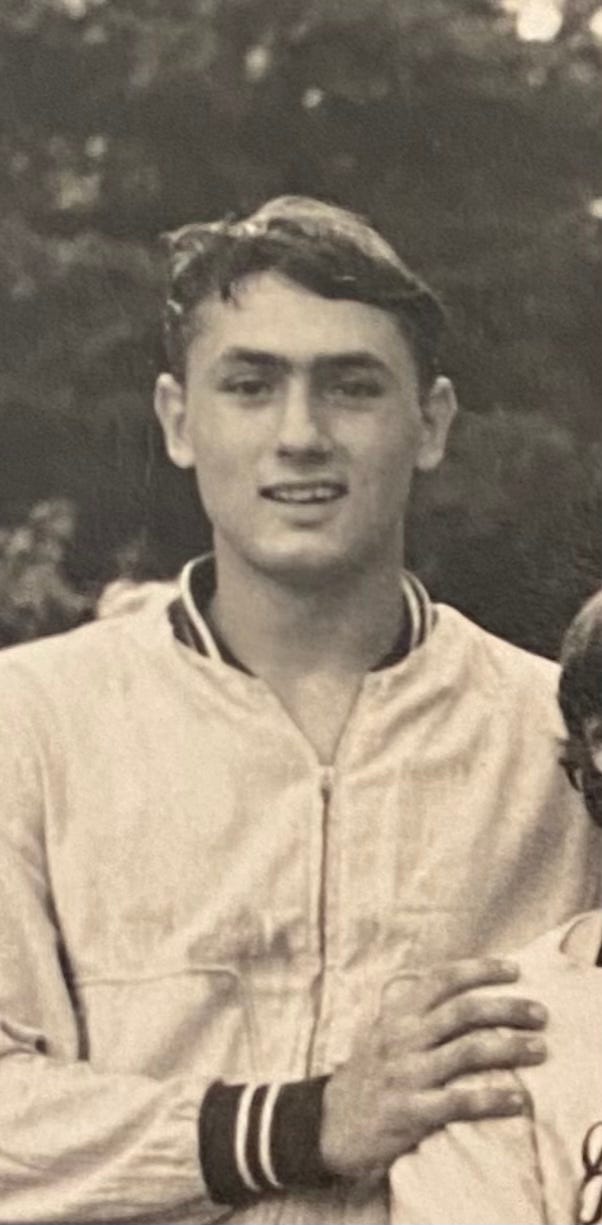

Continuing to flip through, I came upon a photo of Dad, as a young man at a lake beach. He must’ve been about 18 or 19. I carefully peeled the image out, so as not to tear it. Looking at it closely, I saw that Dad was wearing a light jacket, and shorts, with tousled beach hair.

In the image, he was smiling, his famous side-smile, lost in the joys of youth.

“Where’s this one from?” I asked, photo in hand again.

Dad leaned in, “What? Oh that, that’s in the Adirondacks,” he said, his voice lifting, his face lighting up.

“God that was the best Summer… ” he said, leaning back in his chair looking out the window.

“Oh yeah? Why’s that? What were you doing up there?” I asked.

“I got a job up in the Adirondacks at a resort at Loon Lake,” he said, savoring the sound of the double ‘oo’ in ‘Loon.’

And all of the sudden, Dad lost in memory, began rattling off the names of Adirondack lakes, like a savant:

“There was Cranberry Lake, Lila Lake, Schroon Lake, Blue Mountain Lake…”

Cutting in, to stop what I knew would become a lake ramble, I said, “What did you like about Loon Lake, Pop?”

“Oh boy,” he said. “It was the best of times up there. I don’t know, we were all friends. We worked there at this resort over the Summer, and spent time together. It was just a very good time.”

“Loon Lake…” he said, lingering again, lost in memory.

It occurred to me that I’d never heard of ‘Loon Lake’ before, or much about when Dad was a young man.

I was the youngest in the family, and by the time I was 4, my parents decided to divorce.

Things got dicey after that.

There wasn’t a lot of time listening to stories of my parents’ childhood.

And then when I was 13, I was in serious yogic training with my Guru.

These kinds of discussions just never happened before.

It felt new and connective to imagine him as a young man, having bonfires, working a job at an upstate lake, laughing with friends.

Hearing the story of his time in the Adirondacks, I could smell the fresh green maple leaves on the trees. And I could feel the refreshing lake water on my skin.

I asked him, “Did you go back every year?”

“No, no,” he said definitively. Then uncomfortable at the thought, he turned away, saying “I never went back.”

Looking up from the album surprised, I said, “What?! Your best time ever, and you never went back? Why not?”

“Well,” Dad said matter-of-factly, “I got a different job at a construction company,” a slight down turn fell on his voice.

“Doing what?” I asked.

“Nothing, actually,” he said. “Pop Pop had gotten me this easy job at a construction company. All I had to do was get the guys coffee, and bring them stuff. I sat around all day doin nothing. I got paid really well.”

“Gosh, somehow that doesn’t sound great,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said, agreeing.

Then he doubled back defending his father, “What you gotta understand is that Pop Pop worked very hard all his life. He was so proud of that job he got me. He wanted me to go there. So I did.”

“Did you enjoy the job?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“It was ok,” he said, “But nothing was like that Summer at Loon Lake…”

Each time he said the words ‘Loon Lake,’ you could tell he was transported back in time to memories of his friendships and life there.

Riding now by the Adirondack lakes, I’ll tell you, I was doing something intentional in those last years of Dad’s life.

I wasn’t trying to make it perfect, or deny the difficulties he’d put us all through.

I wasn’t pretending, or trying to have everything be something it wasn’t.

I felt genuine compassion for him.

Years before, one day, out of the blue, I asked myself, “What is 25 years of meditation and immersion in yogic wisdom, if you can’t forgive your father, and extend compassion to him?”

And just like that I was ready. So, I called him, and we reconnected.

The thing is, I was 12 when I understood things that took my father a lifetime to understand.

It baffled all of us.

I didn’t hold a grudge about it. I’d accepted it long ago.

Sometimes you incarnate to a person who’s older than you on a body level, and who is younger than you on a soul level.

When that’s the case, it’s confounding, and it’ll take time and effort to understand.

Spending time with Dad, in those last years of his life, I was two things:

1. A daughter, with all the complexities, frustrations, appreciations, losses, joys, and love that go with that.

and

2. Not a buddy, but a friend of sorts. I was interested in knowing who he was, apart from my expectations, and our familial roles. And I wanted to share who I was, who I’d become.

It was a ‘Hail Mary Pass,’ which with my grounding, and his old age, I saw an opening.

So, I dropped back, looked up, and took my shot.

Those were magical days, not because of fantasy, but because of grounding, maturity, and acceptance. It might not be everyone’s choice to do this, but it was mine.

Through that choice, we became known to each other, not just as father and daughter, but as separate people.

No one would’ve noticed, but for us, it was remarkable.

The Gift

One day, while I was with my mother at Sloan Kettering, Ma turned to me and said something that stayed with me.

Seeing my frustration at some inept hospital attendant or doctor, she reached her hand out to me.

“Darling,” she said, her voice full of tenderness, “You’re going to have to accept other people’s limits.”

Meaning when a person’s capacity was low, I struggled to accept that.

Scoffing at her, like a petulant child, I said, “I will not.”

But in the years that passed since, I reflected on what she’d said many times. What it mean’t, and how it might serve in many ways.

Those days with Dad, seeing and accepting his capacity, and my own, Ma was right, it did something.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Seeing Through Yogic Eyes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.